I live five blocks away from what many consider to be the gastronomic corridor of Lima, Peru, a city that is so jam-packed with gastronomic corridors it has about four times the number of restaurants than New York. My neighborhood’s Avenida La Mar boasts 49 restaurants, cafés, and gourmet food shops on a 10-block stretch, and that’s not even counting the eateries that populate the side streets or parallel roads. It’s an embarrassment of riches in a location that, for many Limeños, would never amount to much despite its zip code. For most of my life, Avenida La Mar was not a fine-dining destination. Instead, it was the district’s poor cousin, a disheveled and scrappy spot that straddled the hoity-toity and well-groomed corners of touristy Miraflores and upscale San Isidro.

I’m fascinated by this metamorphosis. To have so many options and amenities within walking distance in a notoriously pedestrian-hating city feels like a blessing, especially since I do not drive and have no plans to ever learn. I also understand that I’m witnessing a form of gentrification, though I don’t quite know what shape that takes in Peru or what its implications are. This sounds like an apologia, but it’s not my intention. It’s an admission that I truly have no idea what is happening in Lima when it comes to housing, development, neighborhood revitalization, city regulations and resources, and every other factor that molds the urban landscape. I know rents are rising, Lima keeps sprawling, and traffic is so bad at peak hours that a 20-minute care ride can easily turn into 60 minutes of inferno.

The media consensus around La Mar’s transformation point to two key moments in the avenue’s restaurant scene. The first was when the Chang-Say brothers opened Pescados Capitales in 2001, a cebichería that stood out for its sleek interior design and late opening hours, drawing a more moneyed and international crowd. The second was super-star chef Gastón Acurio’s decision to open up his casual-ish seafood restaurant, La Mar in 2005 only a few blocks away. He was at the height of his popularity then, the first Peruvian chef to wow San Pellegrino, and the Grand Daddy of what we call now Peru’s gastronomic boom.

There were, of course, a handful of mom-and-pop eateries before these titans of industry LOL staked out a spot in La Mar. La Red, helmed by Isolina Vargas, opened its doors in 1981 as a hole-in-the-wall that my dad used to frequent with my grandma, lured by her chupe de camarones. Her restaurant still exists, growing in size with each passing decade. Grimanesa Vargas, a master anticuchera, spent countless nights firing up her grill on a La Mar street corner. My best friend, Rocío, used to get evening cravings for her roasted choncholi’s (beef intestine) and described this stand with the reverence of someone describing the Sistine Chapel. Now, you can get her savory skewers in her brick-and-mortar.

However, it was odd to see two restaurant behemoths pop up in a not-quite-cute part of town. As Nicholas Gill wrote in New World Review back in 2009: “What’s bizarre about this setup is that there is little that is attractive about the street itself. There’s no ocean view or charming shops. What you’ll find are plenty of auto repair shops and minimally appealing apartment complexes.” (Gill is one of the great food writers on the cuisines of the Americas and you should definitely check out his newsletter New Worlder.)

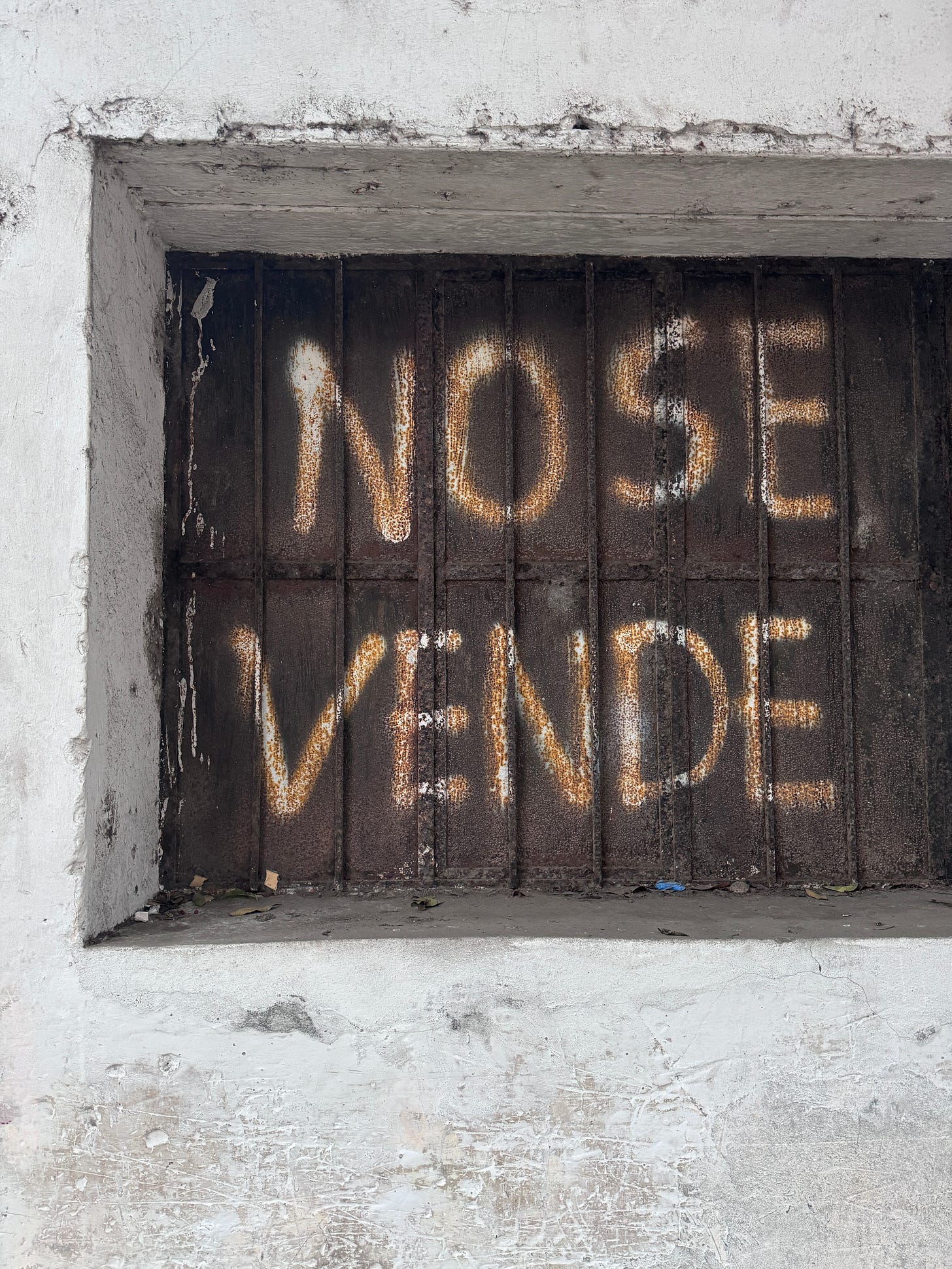

Siete Caníbales, a Spanish-language food publication, recently surveyed the avenue, noting the many celebrity chefs that now have restaurants on its blocks or in spitting proximity: Rafael Osterling, Jaime Pesaque, Moma Adrianzen. While the journalist Ignacio Medina’s tone is mostly breezy and affable, admiring the number of gourmet stores, artisanal fish and butcher shops, and the increasing variety of cuisines you can find on the streets, there is still a nod to what is disappearing: the tiny single-family homes, the small bodega, a long-established but outdated ice cream shop. Bemused, he writes “los habituales toman café y se cortan el pelo con una frecuencia nunca antes conocida1” after observing the freakishly high number of hair salons that call La Mar home.

As for local media, it’s hard to gauge any sort of in-depth analysis about what is going on. (Oooh, the shade!) No disrespect to my fellow Peruvians—and I’m not about to go on an interminable tangent about the dysfunctional media we have here—, but there seems to be an unspoken agreement that when it comes to food in Peru, we shall only speak of it in lauded terms. It only provides net benefits, period.

For any nuance, we have to turn to academics. Dr. Denise Claux wrote about the culinary hot spot through the lens of gentrification in Íconos, a Spanish-language social sciences journal. Her account of La Mar piqued my interest because it offers historical background on how that area developed pre-gastronomic boom. It was the former site of a hacienda that sold the land in smaller and smaller parcels, which in turn were sublet into smaller and smaller areas to lower-income residents. The municipal government pretty much ignored it until the 90s, when it created different public programs and incentives to revitalize the area. These included making mortgages more accessible, implementing certain regulations, and boosting private investment. Coincidently, this occurred right around the same time that Peru’s gastronomic boom began. As a result, La Mar is one of the few spaces in Lima— an infamously economically segregated city—where you can find residents of different socioeconomic backgrounds living and working side by side.

Claux chooses an easily-doxxed bakery owner as her case study. I read the reasons why he chose La Mar with both sympathy and a little bit of cringe. I related to it, begrudgingly, acknowledging all the problematics behind his statements. After spending several years in London and noticing that the city’s “cool areas” were precisely neighborhoods “in transition”, he sought one that mirrored those conditions in Lima. He needed to find a space that was affordable and also unbound by the conventions he noticed in the city’s higher-income neighborhoods, while also being near that clientele. La Mar fit the bill.

I can’t help but think of this as privileged Peruvians importing gentrification from their stints abroad. I also understand what this bakery owner means by needing to find spaces where you are not bound to the staunchly rigid expectations of Lima’s moneyed population. To his credit (and I’m reading this in good faith; I’m not going to fact-check his claims lol), he emphasizes that he turns to the avenue’s carpenters, craftsmen, providers, etc. when he needs to get something done in the bakery and has made efforts to reach out to them, be part of the community. In her conclusion, Claux doesn’t go for the usual binaries that cloud this topic. She acknowledges that people like the bakery owner perpetuate certain power structures while also helping to preserve the La Mar of yore.

I don’t know if I fully understood Claux’s entire thesis, but I took it as this: Shit is complicated! To say La Mar was better before the restaurants popped up is something I would claim to appease a specific type of international gaze that wants to make blanket statements of other areas of the world through their own experiences in Brooklyn or what-have-you. (A gaze that is, quite often, comfortably gentrifying their own cities.) That doesn’t mean I endorse everything about this change or that I am not left with questions about whether old-time residents are better off or not.

So right now, you might be thinking, “Hey, wasn’t this a personal history? Where’s that?” Here it goes.

I’ve lived most of my life abroad, but I did spend a total of eight years living in Lima during my childhood/youth and have frequently visited my family, most of whom have spent the vast majority of their lives in Lima. When I say, family, I don’t mean abuelitos and cousins. I mean parents and siblings. I am the wayward daughter who fled and never looked back. All this to say that while I may have been gallivanting around the world, a family member held down the fort in our home country. And though my family moved apartments more times than I can count throughout my life, our two longest continuing residencies were in my Abuelita Cucha’s house and my parents’ condo in San Isidro, which they bought while I was in college. My abuelita’s place was a block away from La Mar and I can get from my parents’ condo to La Mar on a 5-minute walk.

TL;DR La Mar is the closest thing I have to a barrio in Lima. I’ve seen the changes with my own eyes.

Growing up, I knew it was sketchy though I never thought of it as dangerous. We knew not to go there at night, I can’t tell you why. It’s not like we heard of murders or drug deals gone wrong, LOL. It was rough around the edges, in the sense that homes were humble, buildings looked run down, and there was an eclectic assortment of much-needed but poorly paid craftsmen like carpenters, electricians, and mechanics. My dad says all the crime came from gangs and lowlifes that lived elsewhere; that the actual residents were just hard-working folk. I like to believe that.

La Mar was where we went to buy last-minute school supplies and where we took our dog to the vet. That was all it was up until I was in my early 20s, when I was surprised by the news that Gastón’s massive new restaurant had opened up on the avenue. My mom took me there to lunch, where it was packed to the brim with local and foreign diners, pitucos and more middle-class folks, big families and big company outings. I’m not trying to make this sound utopian; just that the only thing I can say about the demographics of the place was that they could all afford to eat there.

More restaurants kept opening up. Soon, the high rises began. Then, the gyms and hair salons. More cafés. An unnecessary number of ice cream shops, though I bet there are people out there who would argue there can never be too much. The vet is still there. The school supply store is still there. A handful of bodegas are still there. It’s not any cuter than it was before. It looks even more chaotic, to be honest—one super modern but bland corporate building next to a brightly painted tiny home.

I asked my dad if he knew anything about the residents who were still holding on to their homes, despite all the development. THIS IS ANECDOTAL EVIDENCE, SO DON’T YELL AT ME. I wish I had the money to do a massive study, but I don’t. From what he had read and heard, a lot of those tiny homes are caught up in messy legal situations: squatters, homeowners with missing property titles, feuding families suing each other over ownership, an infinite trail of subletters subletting to other subletters that make it nearly impossible to figure out who you would call if you wanted to make an offer on their property. This mess might be preserving the original neighborhood character more than anything else.

I asked my dad if property taxes had gone up with the new buildings. He looked confused. Turns out Peru doesn’t raise property taxes the way cities do in the States. There’s no reassessment. Everyone pays a flat rate based on whatever the original purchasing price was.

I asked my dad if he knew anyone who had sold their home in La Mar to a developer. “No,” he said. “But I do know of people who have sold it in other areas and they’re usually ecstatic. They get a bunch of money, sometimes even a new apartment, and never look back.”

Not everyone is going to feel that way. My dad is not the be-all and end-all of information resources hehe. But I do sometimes wonder if our practical Peruvian mindset, honed by decades of national hardship we’ve gone through—internal armed conflict, dictatorship, a dysfunctional democracy that includes 6 presidents in 4 years, a pandemic that caused one of the highest death rates in the world at its peak, countless human rights abuses, a country so fraught with sexual violence I’ve gotten used to seeing #PaisDeVioladores every day—simply don’t see this an issue. I know too many Peruvians who would laugh in my face if I asked them whether they would reject more money than they’ve ever seen in their life if it meant they could stay in their neighborhood. I know too many Peruvians who would consider that offer a miracle.

A few weeks ago, I started an Instagram account called Eating La Mar without any fanfare. I followed all the restaurants, cafes, and food-related shops on the avenue that had a social media presence but no one else. I have only 9 followers and 3 posts. I’m not sure what I want to do with it. I have no intention of becoming an influencer LOL or the skills to do so. My posts are all over the place, thematically. On one, I’ve gushed about the Peruvian practice of a lunchtime menu; on another, I went off on a super longwinded reflection on Peruvian women turning to baking whenever they need money. My latest is a little ditty about parihuela.

Sometimes I think I should be straightforward and give useful info on the restaurants. Sometimes, I think I should focus on the dish pictured. Sometimes, I think this is the most navel-gazy of all my projects and maybe that’s what I need.

Nevertheless, I had an archival urge to trace what was happening in La Mar. For my own sake. Nothing more, nothing less.

What I’m Reading

Still on my memoir binge! Finished Splinters by Leslie Jamison (beautiful work that could have been an essay), Liliana’s Invincible Summer by Cristina Rivera Garza (impactful, unforgettable, a masterful example of working with archives), and Los Rendidos by José Carlos Agüero (a collection of essays from the son of former Shining Path members, impressive for ability to holding multiple truths one breath and refusing to smooth out any contradictory sentiments around the subject.)

What I’m Watching

Love Island USA, is the best damn show on TV right now.

The Bear. Yeah, season 3 is not as strong as season 2, but it felt like it was a setup for a much better season 4. I loved the episode “Napkins” and the appearance of the 3rd Fak brother.

Under the Bridge. Who knew Canadian teens were so troubled????

Robot Dreams. Way to rip my heart out of my chest, tear it to shreds, while also reminding me that we survive all our losses, we really do. Yes, this is a movie about a dog and a robot who become friends.

What I’m Listening

What I’m Downloading

No new podcasts this month as I keep circling back to the Viall Files and The Run Down on a stress-numb-my-brain loop.

Shameless Self-Promotion

Thanks to all my new minty-fresh subscribers and to everyone still here after my rebrand! Your support means a lot. As a reminder, a paid subscription includes:

Samples of my pitches & rates, applications, and spreadsheets & templates

Weekly, virtual write-ins (resuming next week!)

Access to the full archive (free posts go behind a paywall after a year)

I’m looking to participate in readings/open mics/poetry jams/lit salons/whatever-you-want-to-call-them in New York and Chicago! I’ll be in New York from August 14-Sept 3 and in Chicago from Sept 3-Sept 24. I’m already set to perform at CHIRP’s First Time on Wednesday, Sept 4 and Funny Ha-Ha on Friday, Sept 13 but I want more! Especially in New York. If you know of any or run one, reach out!

Half-hour, virtual Tarot readings are back on! The suggested donation is $40. Books yours here.

If you ever want to peruse all the books I recommend in the newsletter, head over to my Bookshop bookstore!

Translation: “The regulars drink coffee and cut their hair with an unprecedented frequency”

Your description of La Mar reminded me of my old hood of South Jamaica Queens, NY. Specifically, the block I lived on was quiet but it was definitely surrounded by turbulence. If I remember correctly, Queens, along with Brooklyn, is also seeing rapid gentrification with up-scaled restaurants leading the charge. Thanks for your insight on La Mar.

I loved reading your perspective of La Mar. I still dream of Peruvian food often, especially the La Mar cebicheria... getting to know the neighborhood on a more intimate level feels like a wonderful evolution.